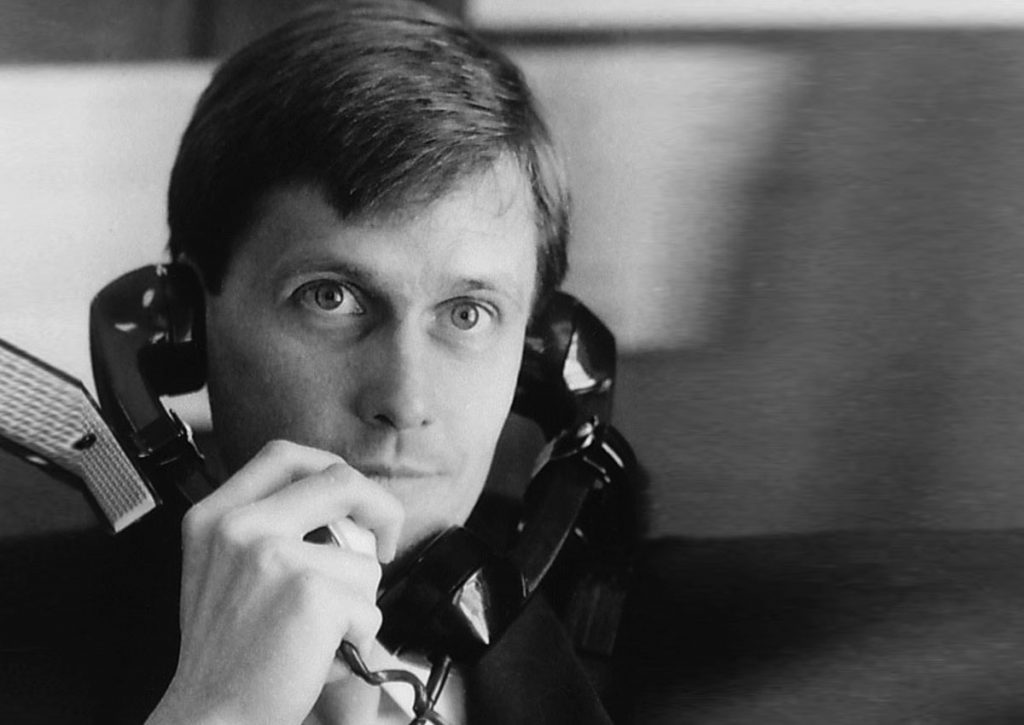

100% Living and Working with John-Roger | An Interview with Ted Drake

NDH: What’s it like working with J-R?

Ted: Well, the main thing is the blessing of working more closely with J-R as a spiritual teacher, because I can’t remember any time when the interactions became just material. He has said, obviously many times, that he never forgets that he’s the Mystical Traveler. That quality was always present in my interactions with him. Although there may have been a materialistic focus, or a task that needed to be done, the quality of teaching, learning, and working with a spiritual teacher was always there.

I guess if there was some time that I forgot that it was present, there was still the quality of upliftment that takes place around him anyway—or with him on the phone, or reading his email. I could be very confused about something and I would sit down to write an email to J-R about it. Just that level of involvement, writing an email with no response yet, could completely clarify the subject, or it could enlighten me as to what I needed to learn or do in order to clarify.

I enjoyed watching him interact with other people and watching him transform or transmute negativity in a situation, and watching how he could find or create a point of balance in any situation. One of the most frustrating lessons in working with him, or just observing him, would be that I would see an out of balance situation, and either I would tell him about it, or I would realize he already knew about it…and I’d keep wondering, “Why don’t you fix this J-R?” Sometimes I’d be in that situation for many years, more than a decade. Then I would observe when he would finally bring it into balance and I would think, “Okay, so why did it have to take this long before he would balance it?” I don’t remember ever asking him, but generally the answer inside of me seemed to be that if he had balanced or cleared the situation sooner, someone, generally one of the main protagonists, would not have been ready to learn the lesson that was there for them.

It’s helped me with my impatience a little bit [laughing]. At least I got a better understanding that what some of us may have perceived as an annoying imbalance was for at least one of us, usually a protagonist, a very important lesson, and that learning was the greater priority.

NDH: When you said he could find the point of balance in any situation, what did you mean by that?

Ted: Generally, if two people are experiencing an imbalance, I’ll look at it and start questioning. Is the balance more towards this person or that? How far in each direction? Of course, that becomes much more complicated when there’s more than two people involved in the same game. Where I saw this most dramatically was house meetings at Prana. We would be trying to make decisions and usually there were two sides. It wasn’t always that simple, but if we take that as an example, if a person presented on behalf of one side or against the other, it seemed as though nearly everybody in the room might have voted with that person at that time, but then when the next person presented they might have moved to the opposite side. People would be so swayed.

J-R always seemed to be able to resolve that, and when we made decisions at Prana—and this could be true in any group—sometimes I would think afterwards, “Well yeah, but if it had gone this way instead of that way…. ” But when J-R brought us to the point of balance, it was so joyful to watch how well it was resolved inside of each participant. It was kind of a sublime resolution usually. Maybe always.

NDH: How did you first meet J-R?

Ted: It was 1970. I was dying, and it appeared (and J-R confirmed this later) that I probably had months left to live. My body was incapable of detoxifying at that point. The normal onslaught of toxins that we all experience every day, but generally clear, was killing me. At the time I was in Miami and I thought in order to take care of this it might work a little bit better if I moved to New Zealand because it is less polluted. I didn’t know what else to do. When I went to buy the ticket, the travel agent said, “You have to overnight somewhere and your choices are Pago Pago or Los Angeles.” and I asked her a little bit about Pago Pago. I had already heard about J-R, and that there were taped seminars in Miami, but somehow I never did any of that. I picked the flight that had an overnight in Los Angeles. I thought I might as well recover from a little bit of jet lag, so I decided to stay for a while.

A friend introduced me to J-R. So right now, I guess, it’s been about 46 years between flights. At the time, I had a bunch of things wrong with me. One is that I had osteoporosis so bad that if I would knock on a door, my hand would hurt for days. My spine had started to curve—scoliosis. I had gone to Massachusetts General Hospital and I was told that I had to have what they called a spinal fusion. Which is no big deal nowadays, but back then the doctor told me that it would take six months, flat on my back in the hospital, without leaving the bed, to recover from the surgery. He said that I had a zero percent chance of reversal of the curvature. I would never have a straight spine again, and I had a 30 percent chance that the procedure would be successful and arrest the curvature, so that it wouldn’t get any worse.

I had this coating on my large intestine. When I met J-R, all that stuff got reversed. I had a far worse condition than just imminent death because my attitude was so bad. I actually thought that the world was coming to an end because what I observed around me was getting worse and worse all the time. It never dawned on me that it was my own creation and my own perception that was creating all that. Fortunately, that was reversed as well. Or I should say largely reversed. I’m still working on it now.

J-R gave me a special diet in a light study and he also told me to get chiropractic adjustments. He said the diet would help me rebuild the bones and he did a whole bunch of other things as well. It was delightful. He said that if he straightened out my spine immediately, I would die from the pain. He said, “Have a series of adjustments to get it fixed up.” At one point, I had to switch chiropractors. The new one did an X-ray as part of his intake procedure. After he took the X-ray, I told him about the scoliosis, and he said, “That never happened. That’s totally impossible. Your spine could not be this straight if you ever had scoliosis.” I just kept quiet. The spine is still fine today.

NDH: What were your first impressions when you came to L.A.?

Ted: When I looked at J-R’s personal staff, I sensed that they knew or had something that I didn’t know or have. Which was inspiring. More important than that, somehow inside of me I knew that if I stuck around, then that might be imparted to me as well. Prior to that, I had lost a sense of direction. Since I was a little child, I’ve always been interested in learning, so it seemed to translate to “what do I learn now?” I remember spending a long time in the stacks of the library of Columbia University, just looking, like “what do I learn now?”

I was looking at books on meditation. When I looked at one book on mantra yoga. I thought, well that seems boring. That was as far as I could get with it. I wasn’t able to discern that there might be different levels of that. I thought I was able to discern the input process, but I wasn’t able to discern the product or the outcome. I was incapable of making that choice at that time. But when I met J-R I realized I had made a choice that seemed to happen overnight. I kept thinking I want to stay a little longer on that stopover… and then I realized I wasn’t leaving.

NDH: What kinds of things did you learn from J-R?

Ted: That question sounds impossible. I want to talk about a couple of things that come to mind. When I said it sounds impossible it’s just because that’s so constantly what was going on. I had been brought up to live a mostly materialistic existence. Supposedly more money is better than less, and a longer life is better than a shorter one—all these conditions and qualifications—but he was giving me a whole new set of reference points for all of that.

One day, I got stuck and I was seeking direction. J-R showed up physically and he told me the solution. I said, “Why didn’t I think of that?” Later on he explained it: “The only difference between you and me is attitude. And that’s the only difference.” I not only wanted to change my attitude, which I already did before he said that, but I started methods, including decades of doing innerphasings and the “Do it Now” meditation with the affirmation, “I focus on God”.

NDH: Was it easy to work for him, or demanding? Were there certain patterns or styles of work that you noticed?

Ted: I think any person you work with is going to have a different mix of those two things. The difficulty each person presents, or the set of difficulties, is going to be different. Sometimes I’ve experienced kind of a fear or an anxiety, which is something I tend to create, but most of the time, I’ve experienced a tremendous amount of support. The most unusual aspect of the support was the extent to which he did not condition what I could bring up with him, what I could talk to him about, what I could ask about, or areas in which I could request assistance. There was no conditioning or conditionality.

During the whole time I knew him I never saw him take a position of superiority over any other person. This aspect of openness in the relationship was truly astounding. And I tried to be as open in return. I remember once at Prana someone told me something and said, “Do not tell J-R.” As soon as she left the room, I picked up the phone and called J-R, and started telling him about it. He said, “Why are you telling me this?” As I started to answer him, he picked up on me. He said, “Oh, I get it.” It’s like, if I did not tell him it would raise the question of whether I value my relationship with her more than my relationship with him. I told him just to clear myself. Not because I thought he really needed the information.

He was open to any kind of communication on any level. When I was talking to him, I always perceived that I had his attention. When I sent him an email, he always had time to read it. I never heard of anyone working with him where there were any exceptions.

He always had time to listen, to discuss. Sometimes you’d have to wait, but there was never anything for which he said, “I’m sorry, I don’t have time for this.” He was always present when I was talking to him.

More than anyone I’ve ever observed, he had the humility and the flexibility to work with a person the way that person needed to be worked with. Sometimes I would see another staff person do something and I knew I would never get away with that. John Roger would just tolerate it repeatedly with no comment. Each person was treated individually.

The working style I noticed was flexibility and humility. When I say humility, in case that’s not extremely obvious, most people will take a stand, like, “Someone really needs to treat me in this way.” J-R would just surrender and deal with the person where that person needed to be dealt with. So you might say that rather than having a certain style of doing things, he lacked style more than anyone, and I consider that a great accomplishment.

He was pretty dramatic in making the point of his devotion to each of us as an individual. It was a high level of dedication to having the flexibility and the humility to come to each person’s level. Often you could see the shift when he turned his focus from one person to the next, and if the other person would change, then he would too. His whole expression would change. It’s really an admirable, beautiful example.

Many times when I needed to handle a situation and I had a hangup, I wouldn’t recognize it then. But years later when I would get past the hangup and look back at that situation, I realized how kind, how considerate John-Roger had been. Just to let me have a hangup until I was ready to get rid of it, and to assist me in solving a problem in the way that I thought I needed to solve it.

NDH: It’s a detachment because it seems like there was nothing pulling on him in the lower worlds.

Ted: It didn’t pull him in enough to do it. You see, if there’s nothing pulling on him at all, then his behavior would not be so exemplary. But if he was thinking, “I’d rather have better food and be able to be served…and I’ll sacrifice that,” that’s what makes his behavior so amazing. What I saw was sacrifice and willingness to let go.

NDH: So it wasn’t like an absence of karma. It was like a letting go of the karma.

Ted: Amen. Which to me is much greater. If Jesus was perfect, then perhaps we could conclude that he accomplished nothing here on earth, and that what he did was no big deal; but by describing Jesus as imperfect, it does two things. First of all, it tells us yeah, he did have things that he suffered with and had to overcome in order to complete his ministry. And the more important lesson to me is, if he was perfect, then we have a perfect excuse for not doing what he did, but if he was imperfect like us, we can’t pretend that limitation. That’s how I look at J-R also.

NDH: Did you ever see him out of balance?

Ted: Oh yeah. Yeah, plenty of times.

NDH: In what way?

Ted: A number of times, I’ve seen him take a certain approach with someone. Then whatever approach he took, obviously that person was reacting to that approach. So he was creating a block instead of healing and fixing. I was amazed to watch the speed with which he would backpedal, the extent to which he would backtrack. He would not even worry about completely doing a 180, and contradicting himself, and taking an entirely different approach, which then worked with that person.

What you’re asking has been recorded many times. So often when I would see him doing that, I would think about how difficult that would be for me, how humiliating it would seem to me, to boldly assert one thing, and then when a person objects, just equally boldly say the opposite. I guess there seems to be some kind of rigidity in me, where I would watch and say, “I don’t think I can do that.” But his service to each person was so powerful and so dynamic.

Sometimes, if I had a concern, he voiced it for me if I hadn’t said enough about it, even if no one else was concerned.

NDH: Did he do a lot of explaining of things or was it mostly by example?

Ted: By example. He often told us that he doesn’t tell us every last word. There are things he said that it’s taken decades for me to understand. By surfacing the issue, eventually the learning takes place.

He has spoken repeatedly about how he likes to surprise people, and he enjoyed the fact that he could do that. He was willing to go to so many different levels to break people free.

NDH: Has it been different for you since he’s died?

Ted: Around the first of October in 2014, shortly before he passed away, I woke up in the morning and I couldn’t find John-Roger inside of me. On one level it was just a predictable panic, “Where’d you go? What’s up?” This had happened to me so many times before. It first started happening way back in the early ’70s. The first time it was a big thing. Each time this happened, it was usually within a few days when somehow, I’m bumbling around inside my consciousness—like I don’t even know what I’m doing—and suddenly, “Oh there you are.” That’s the first part. Then the next part is I somehow come to the conclusion that I’ve accessed him in a higher place inside my consciousness. Now, if you ask me, “Where did you go to find him and how did you do it?” I’ll say, “I have no idea.” If you ask me what made you think you were in a higher place inside your consciousness, I have no clue. None. That’s somehow what I’ve concluded.

The second time it happened was a little bit less frightening, and now it’s been going on many times. So when it happened around the first of October in 2014, my concern or ambivalence was minimal. But later in the day I noticed I couldn’t find Jesus Christ inside of me either. At that point, it was much more of a panic because that hadn’t happened before… and so I became quite a bit more concerned about what was going on. My habitual response was, “What am I doing wrong?” This doesn’t make this process any easier. Generally, this would be resolved within a few days with J-R. But this time it wasn’t. That was the point at which I became more concerned what was going on.

This continued for days. Then I remember that specifically with Jesus Christ, he didn’t always have to be in me as Jesus Christ. He could also be in me as me. I had been in groups in MSIA in which Jesus Christ was working in us and through us, as us—each person in the group. There is no “other” recognizable as Jesus Christ when he does that. I’ve been able to confirm those experiences with J-R, so I guess he was preparing me for this event at the beginning of October in 2014.

When I reflected on what I was experiencing, I’m like, “Oh, maybe these guys aren’t gone. Maybe they’ve shifted from a personal presence as themselves to this mode that Jesus Christ had been using, functioning in us and through us, as us.”

I realized I had to shift to a higher level of discernment in order to figure out whether in fact that was taking place again this time. One clue that had seemed to be present each time in the past was a more consistent sense of service. There was a level, a vibration that was positive and that would hold in a way that it didn’t at other times. It just seemed like “me” but operating on a higher level.

In the past this has always seemed to take place as a group action so I have no reason to think that anyone is excluded from what I’ve been experiencing. Jesus Christ may be working in every single one of us and through each of us as each one of us right now. That’s what would surprise me the least, and this action may gradually unfold, amplify, and become more obvious as time goes by.

NDH: What did you learn from watching J-R at work in different situations?

Ted: One thing that I saw him do was that he practiced a form of openness within the organization. He really encouraged us to be very inclusive when we would send emails, for example—including everyone who would be concerned as a result of the decision-making process. I don’t remember him ever saying don’t include. I would see him take an email with a short address list and add to the address list. (Now, if he was saying something personal, often he would just communicate it personally.)

I remember when we were working on a conditional use permit for the Windermere property. It was a small group that was included in that process, but J-R addressed all of the staff, and he said, “I want input from everyone.” He didn’t ever seem to be one to have an elitist perspective. Everyone was equally included and equally considered. It didn’t matter who brought up a question, he would want it to be addressed.

Now there were certain times when people would take a very obvious and generally self-confessed position of opposition or againstness. I’m not talking about that. I perceive a difference between power and control. Power is like love. You gain power by giving it away, by empowering people. If you just look at the English, how do we talk about control? You take control.

He said that someone asked him, “J-R how do you handle so much?” He said something like if someone brings me something, I figure they can handle that. If a person brings forward an idea, it’s their idea and J-R wouldn’t take that from them. Then if more than one person became involved and there was a dispute, he wouldn’t have to take it from that person or those people. In a way, with notable exceptions, the ball was never in his court. As soon as there was something for him to handle, he would handle it—generally, giving it back to the person or the persons who were carrying it at that time.

NDH: I think you’re saying if someone came up with an idea to do something, he would say, “Yeah, sure, go ahead and do it,” to have them complete the action.

Ted: Correct. He was never taking control of anything. He was always empowering. As long as he sticks on that side of the equation, there’s never a burden on him.

NDH: The way I see it, I always relate that to J-R’s triangle of manifestation, where he says for every thought, have a feeling and action to match. That’s the way action is balanced in the physical world. If someone’s coming up with the idea, what they have is a thought and a feeling, but without the physical action to match. It creates an unbalanced situation. It’s almost like he’s balancing the situation by saying, “Okay now go do it.” J-R has also said that ego is thought and feeling together. By taking the physical action you’re in a way undercutting the ego, because once you’ve completed it in the physical world, it’s out of the realm of ego.

Ted: We have an idea in our culture of what we might call a business ethic, as different from other kinds of ethics. It’s as though there’s an ethics in one area like business, and there’s another set of ethics for criminal justice or the military for example, and another set of ethics for other areas. That had been so engrained in me, but I kept noticing something different in J-R. For a long time, I noticed that whenever something happened or was done that seemed adverse to somebody, or they were going to lose in the situation, I found that J-R would question it. At first I didn’t know what was going on. Then it began to seem that although he often spoke as though he had a business ethic—like you go to work, you do what the boss tells you, and that’s all there is to it—he wasn’t talking to us that way. J-R seemed to challenge my idea of business ethics.

I remember one of the first lessons in this area he gave me was in 1971. He gave me a copy of a book, Mellinger’s Guide to Mail OrderMarketing. The main point of the book is that it was a rigorous, thorough, clear lesson in objectivity. Mellinger had put himself through college by publishing a little ad, and he spoke about how he had a bunch of layouts and he thought he might choose what looked like the best one. It failed miserably, and he picked another one, and it failed, and he picked another one and it failed. Eventually he picked one final one and it succeeded. In each case, he kept careful track of what that ad brought in, and laid all of the others that had failed next to it. He asked himself, “Okay, what’s better about this one?” He could find nothing. There was nothing within his consciousness that said, “That’s why that one would work.” His conclusion, which I consider very smart, was that what succeeded was the objectivity when he tested each one and then picked the one that worked.

On a superficial level, J-R was giving a lesson for success through objectivity. Not just objectivity, because you can be objective without bothering to measure—but taking the measurements that give you the optimum amount of data on which to exercise objectivity. Years later, I had the thought that success is being open to and making use of feedback.

More recently, I realized that sure, J-R was teaching us how to succeed, but he was also teaching us how to be more loving with each other while we’re working together. Often what I observe as a decision-making process is this: One person thinks we should do A, and another person thinks we should do B, and the more dominant one wins. As long as we eschew or avoid feedback, we’re pretty much stuck with that. It puts us close to the level of an animal.

The successful path may or may not be chosen, but we know what we’re choosing out of. We’re choosing out of the area of the Christ, where we’re all equal, and we’re choosing more into the mammalian level, where someone’s going to dominate someone else. The more we can open to feedback, the more we can focus our decision-making process on the use of objective feedback. Then anyone can contribute to the direction of the group and anyone can be right. No one will ever be proven right unless objective measurements are taken.

I never saw J-R deviate from that way, which is non-inflictive, and which creates a certain level of objectivity. If we set as priorities getting feedback, and making choices on that feedback, then we’ve got a much better chance at success and we can treat each other as equals.

Because of the way I was brought up, I didn’t learn to bond with anyone. So when there was a difficulty or a relationship didn’t seem to work, the easiest solution was to fire somebody. Each time I did that, J-R would question me. Then he would have me talk to the person and get that person’s point of view on our relationship. I would learn not to just casually drop a relationship because it seemed like the easiest thing to do, but instead try to act like a person who’s bonding in a community—even if I’m not. Also, each time I did what he said, which was sort of like what we would formally call an exit interview, I would receive from the other person a message that seemed to be out of left field, and my reaction was, “I didn’t know that was important to you.”

In a family, for example, you’d be expected to consider each person’s emotions equally or almost equally. I hadn’t been considering their emotions at all—or even been aware of them. This is subjective, but sometimes during the exit interview, the person wouldn’t say too much at all. Often at Prana when people were asked why they were leaving, they’d say they were just moving on. When I got answers like that – and this is subjective – John-Roger seemed to be disappointed, or would just say something to indicate that he didn’t get the whole story.

Where this is played out the most in our society I think, is in areas like military, business, bureaucracy, and criminal justice. That’s where I got my idea of business ethics—a high tolerance for a huge gap in control of the relationship, meaning inequality. In my perception, J-R was trying to heal that and bring it into a balance. If you go back to the Mellinger example, if you can isolate with good accounting the systems, and procedures, the products, the policies, the people that succeed, little or no additional interpersonal discipline seems to be required.

NDH: Were there other examples of how J-R promoted family ethics, or group ethics?

Ted: I’ve perceived people stealing from J-R, taking things physically. I’ve perceived people who were simply not pulling their weight, not doing their job. I’ve perceived people performing acts of sabotage. Even to the extent that people would receive feedback, as I mentioned before, he might wait for more than a decade until he was sure that that person could take the feedback well and understand the mercy in his intention.

NDH: Yeah, it seems like he is just allowing people freedom and forgiving. Both freedom and forgiveness.

Ted: Amen.

NDH: It’s according to each person’s karma and allowing them to learn the lessons and their karma.

Ted: Right. Freedom, forgiveness and empowerment.

NDH: I also heard of one person who left staff after working for MSIA for quite a while, and he told somebody else, “I’ve been trying to get rid of that person for years.” He never did it outwardly. It’s like for him to do it physically would be to enter into the karma.

Ted: Well, maybe. He explained that to me once. We had a meeting and he said, “I’m going to fire that person.” I don’t know what level this came from, but I said, “No you won’t.” He said, “Yes, I’m going to fire that person.” I said, “No, I can’t see you doing that.” He said it a third time and I said no a third time. I don’t know where I was coming from with all that, but some level in me was convinced. He never did fire the person. Later he explained it to me. He said, “You know, what I do when I fire someone, is on the other side I’ll hold a bauble out in front of them and then they are attracted to it and they follow that.” In other words, if you think that this bauble is better than working with him, okay. He observes that the person is choosing out of the relationship and then he enables that person to ground that choice by quitting and going to something that seems more attractive.

NDH: Then it’s a free choice rather than a situation of force.

Ted: Often I would look at J-R, and look at myself, and ask, “What’s the difference?” The main thing I noticed—and that doesn’t mean it’s the main thing that he is, but what I noticed—was his willingness to do what’s called for with that person, in that situation, at that time.

NDH: Obedience to the Spirit.

Ted: When I look at him, I go, “Wow, that’s the lesson.”